The call arrives in the dead space between meetings. The caller ID is clean. The cadence is familiar. A voice you know asks for a small, fast exception. You hear the pen click, the throat clear, the little pause they always take before numbers. You don’t hear the edit. You don’t hear the model.

This is what the modern con sounds like when it walks into a small company’s day. Vishing used to be clumsy. It’s not anymore. The FBI now describes “vishing” as malicious voice messaging that increasingly “incorporate[s] AI-generated voices,” a sibling to smishing and spear phishing that rides existing trust to new places (Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI], 2025). If that sounds theoretical, it isn’t. The format is already inside politics, finance, and the work chat where you approve payments. In January 2024, a robocall that mimicked President Biden’s voice told New Hampshire voters to “save your vote for the November election,” and one recipient said, “I didn’t think about it at the time that it wasn’t his real voice. That’s how convincing it was” (Swenson & Weissert, 2024). The lesson isn’t about elections. It’s about how quickly synthetic certainty slips past our guard.

Why this works on smart teams is simple. Audio is intimate. We forgive its glitches faster than we second-guess its source. In 2023, McAfee surveyed more than 7,000 people worldwide: one in four had encountered an AI voice-cloning scam personally or through someone they knew; 70% said they were either unsure they could tell a fake or believed they could not; and of those who received an AI-cloned message, 77% reported losing money (McAfee, 2023). The report’s framing is blunt: “With very little effort a cybercriminal can now impersonate someone using AI voice-cloning technology, which plays on your emotional connection and a sense of urgency” (McAfee, 2023, p. 6). That combination—urgency plus intimacy—doesn’t just defeat training slides. It defeats the moment when you usually slow down.

At work, the clone rarely acts alone. It’s part of a kit. Microsoft’s threat team watched a financially motivated actor they track as Storm-1811 abuse Microsoft Teams and the built-in Quick Assist remote-support tool, using “impersonation through voice phishing (vishing)” to shepherd victims to controlled access, then to credential theft, then to ransomware (Microsoft Threat Intelligence, 2024, para. 20–21, 34–41). Red Canary’s June 2024 threat brief echoes the choreography: vishing calls that pose as help desk; email floods to create a problem worth “fixing”; messages from what looks like internal IT to legitimize the ask (Red Canary, 2024). The voice is the glue. It closes the distance between “weird” and “urgent.” It gets you to press the key combo that hands them your screen.

Executives aren’t special here. They’re just searchable. A Fortune 500 CEO’s interview on YouTube and a founder’s panel on LinkedIn produce the same raw material for cloning. A WhatsApp message from “the CEO” becomes a narrow-band transfer attempt. When criminals tried to impersonate Ferrari’s chief executive, MIT Sloan Review reported a “close call” stopped only when a staffer asked a question that a real CEO would casually know and a clone would miss (Galletti & Pani, 2025). In another case, the British engineering firm Arup confirmed a deepfake video conference in Hong Kong that used both fake faces and fake voices to convince an employee to push HK$200m across fifteen transfers. “The number and sophistication of these attacks has been rising sharply in recent months,” Arup’s CIO said after the incident (Milmo, 2024, para. 11). You can feel the shape of the pitch: a familiar voice, a legitimate platform, an invented emergency, and a narrow window that punishes consultation.

With very little effort a cybercriminal can now impersonate someone using AI voice-cloning technology, which plays on your emotional connection and a sense of urgency” (McAfee, 2023, p. 6)

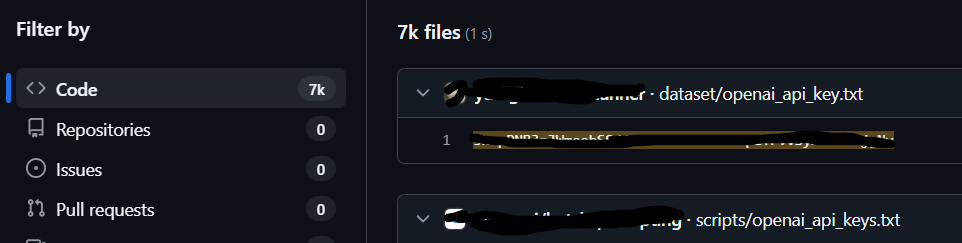

Founders and SMB leaders live inside those windows. You’re shipping, hiring, fundraising, refunding. You know what your CFO sounds like when a vendor is stuck on net-30. You know how your biggest customer talks when they’ve escalated something to you personally. The model learns it too. McAfee’s analysis notes that “with just a few seconds of audio” pulled from social platforms, attackers can “create a believable clone that can be manipulated to suit their needs” (McAfee, 2023, p. 6, 9). A few seconds sounds harmless. It isn’t. The model doesn’t need perfect fidelity. It needs enough to trigger your pattern-matching and nudge you into action.

There’s a second reason vishing lands: it preys on office choreography. Email is the paper trail we audit. Chat is the hallway we tolerate. Voice is the shortcut we trust. That trust was earned when the company was ten people and the payroll system was a spreadsheet. The context changed; the reflex stayed. Microsoft’s 2025 Cyber Signals brief puts it plainly: social engineering “circumvent[s] security defenses” by walking past them, not through them (Microsoft, 2025). Voice is a hand on the shoulder. It doesn’t look like an attack. It looks like work.

It also scales. The image we hold of a “con” is artisanal—somebody calling and calling until they find a mark. That’s over. Attackers stitch together phone trees, LLM-drafted scripts, and synthetic voices into repeatable operations. McAfee’s researchers found “upwards of a dozen free and paid tools” for cloning, and reported that with additional tuning they produced an “estimated 95% voice match” (McAfee, 2023, pp. 15–16). Microsoft saw Storm-1811 run the same beats across organizations: voice-led impersonation, Quick Assist access, batch-scripted payloads, then lateral movement and, often, Black Basta ransomware (Microsoft Threat Intelligence, 2024). What feels bespoke to you is just good manufacturing.

If this makes you picture only the C-suite, widen it. The most dangerous voice in your company might be the one that sounds like helpful IT. Red Canary describes attackers who “masquerade as tech support,” sometimes after flooding inboxes with subscriptions so the fix seems welcome (Red Canary, 2024). The call is structured to lend you relief. The relief is the trap.

“I didn’t think about it at the time that it wasn’t his real voice. That’s how convincing it was” (Swenson & Weissert, 2024)

Outside the office, the same mechanics spill into civic life and come back to work through culture. The Biden robocall in New Hampshire wasn’t after wire transfers or admin passwords. It aimed at participation. “That’s how convincing it was,” a voter told the Associated Press (Swenson & Weissert, 2024, para. 160–161). The tech didn’t care if the target was a grandmother, a founder, or a procurement manager. It cared about a strong voice with a known cadence. It cared about urgency. It cared about the reflex to obey.

What does awareness sound like for a founder in 2025? Not a playbook. A picture. Picture the next “quick call” as a composite: pieces from your last all-hands, pieces from a podcast you recorded, pieces from a YouTube panel. Picture it dropping in right when a customer escalation is burning through your day. Picture a Teams ping from “Help Desk” arriving between the call and the follow-up email to keep you moving. Picture the first script: “We saw the email flood. We can clear it. Just hit Control-Windows-Q and read me the code.” Microsoft documents that exact sequence ending hours later with credential theft and hands-on-keyboard, the voice long gone, the blast radius just beginning (Microsoft Threat Intelligence, 2024). The moment to notice was the voice. Not because it sounded wrong. Because it sounded right.

Small companies are especially exposed because everyone is close to the money. The person who answers the phone can move funds. The person who runs vendor ops has admin in the ERP. The systems that bigger firms wrap in process live in your calendar and your habits. “Smishing” and “vishing,” the FBI warns, are now used “to establish rapport before gaining access to personal accounts” and to push targets onto attacker-controlled links or platforms (FBI, 2025, paras. 2–4). Rapport is the product. The voice is the delivery.

If you want an image to keep, take Arup’s. A video conference with “many participants,” each face and voice familiar enough to make a HK$200m mistake feel reasonable (Milmo, 2024, paras. 18–19). Now collapse that into audio only. No artifacts to watch. No lips to mistrust. Just the cadence of someone you know asking you to do the thing you’ve done a hundred times—the world’s easiest social engineering problem disguised as your normal day.

There’s a quieter truth here too. We talk about detection like it’s an IT feature. It’s also a human limit. When McAfee asked if people could tell the difference between a loved one’s voice and an AI-generated one, most couldn’t say yes with confidence (McAfee, 2023). That’s not failure. That’s how empathy works. We’re supposed to recognize the people we care about. Vishing repurposes that reflex for speed. The business impact isn’t only the wire that moved. It’s the way a team starts to doubt its own ears.

You can see the shape of the year. In May 2025, the FBI warned that senior U.S. officials were being impersonated in AI-voiced campaigns, framing vishing as a technique criminals use to pivot you onto controlled ground (FBI, 2025). Microsoft’s April 2025 signal report foregrounded social engineering as the path around security, not through it (Microsoft, 2025). Journalism found the edges: a Ferrari near-miss; an engineering firm’s expensive lesson; a primary day riddled with synthetic certainty (Galletti & Pani, 2025; Milmo, 2024; Swenson & Weissert, 2024). The arc is steady. The tools get cheaper. The voices get closer. The calls keep coming.

A familiar voice isn’t a second factor. It never was. It just felt like one. That’s the exploit.

References

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2025, May 15). Senior US officials impersonated in malicious messaging campaign (Alert No. I-051525-PSA). IC3.gov. https://www.ic3.gov/PSA/2025/PSA250515

Galletti, S., & Pani, M. (2025, January 27). How Ferrari hit the brakes on a deepfake CEO. MIT Sloan Management Review. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-ferrari-hit-the-brakes-on-a-deepfake-ceo/

McAfee. (2023, March). Beware the Artificial Impostor: A McAfee cybersecurity artificial intelligence report (PDF). https://www.mcafee.com/content/dam/consumer/en-us/resources/cybersecurity/artificial-intelligence/rp-beware-the-artificial-impostor-report.pdf

Microsoft. (2025, April 16). Cyber Signals Issue 9: AI-powered deception—emerging fraud threats and countermeasures. Microsoft Security Blog. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2025/04/16/cyber-signals-issue-9-ai-powered-deception-emerging-fraud-threats-and-countermeasures/

Microsoft Threat Intelligence. (2024, May 15). Threat actors misusing Quick Assist in social engineering attacks leading to ransomware. Microsoft Security Blog. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2024/05/15/threat-actors-misusing-quick-assist-in-social-engineering-attacks-leading-to-ransomware/

Milmo, D. (2024, May 17). UK engineering firm Arup falls victim to £20m deepfake scam. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/may/17/uk-engineering-arup-deepfake-scam-hong-kong-ai-video

Red Canary. (2024, June 20). Intelligence insights: June 2024. Red Canary Blog. https://redcanary.com/blog/threat-intelligence/intelligence-insights-june-2024/

Swenson, A., & Weissert, W. (2024, January 22). New Hampshire investigating fake Biden robocall meant to discourage voters ahead of primary. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/new-hampshire-primary-biden-ai-deepfake-robocall-f3469ceb6dd613079092287994663db5