The logo looks right. The docs feel familiar. A few lines of code and the “AI” starts talking back. That’s how it begins for a lot of founders right now. Not with a spear-phish but with a developer experience that looks just trustworthy enough to ship. The trap is quiet, modular, and friendly. It lives in your dependency tree, your browser extensions, the shiny “API” you wire into a weekend prototype and then forget.

The market made it easy. Open ecosystems move fast and welcome newcomers. By mid-2024, Sonatype said it had logged 704,102 malicious open-source packages since 2019, calling it “malware & next-gen supply chain attacks” spreading through registries at scale (Sonatype, 2024). “We have logged 704,102 malicious open source packages,” the report notes, tying part of the surge to AI-driven demand and spam (Sonatype, 2024).

A friendly SDK that steals your tokens

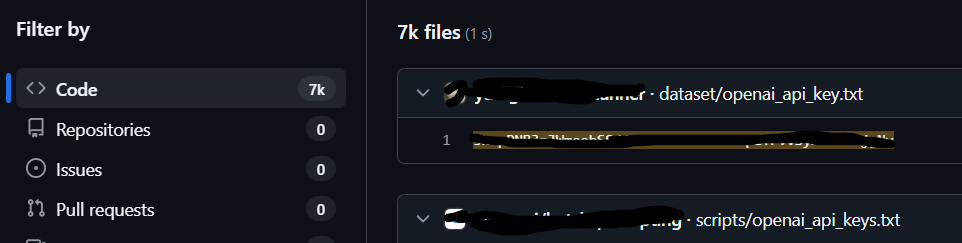

In late 2024, Kaspersky documented a campaign hiding an infostealer inside Python packages posing as AI helpers, including ones themed around ChatGPT and Claude (Kaspersky, 2024a; 2024b). The family they analyzed, “JarkaStealer,” was designed to harvest credentials and developer secrets once a package was installed and executed during normal setup. As Kaspersky’s researchers put it, “This discovery underscores the persistent risks of software supply chain attacks” (Kaspersky, 2024a).

This is the new default for the Trojan stack. Impersonate a useful SDK. Publish it with a believable name. Trigger on install or on import. Exfiltrate environment variables, browser cookies, cloud tokens, or SSH keys. Sonatype’s 2024 analysis describes a class of “data exfiltration” packages that “read… environmental variables, authentication tokens, password files” and leak them out to attacker servers (Sonatype, 2024). That is not theoretical. It is the business model.

The registry itself flinched

The stress is visible at the platform level. In March 2023, the Python Package Index paused new user sign-ups to deal with a malware wave. In March 2024, it did it again. As BleepingComputer reported, “PyPI has suspended the creation of new projects and user registrations” to contain an active flood of malicious uploads (Toulas, 2024). When a software registry hits the brakes, founders should hear it as a siren.

Attackers are also skipping the real registry entirely. On July 30, 2025, researchers warned of a counterfeit PyPI website built to phish Python developers and push Windows malware through drive-by downloads and fake instructions (Gatlan, 2025). The counterfeit site mimicked branding and search behavior so that a harried dev—vibe coding late at night—would not notice the edge-case typos or the missing TLS nuances before pasting an install command.

The browser is a supply chain too

Not every Trojan ships through pip or npm. In March 2023, a fake Chrome extension marketed as “Quick access to ChatGPT” hijacked Facebook business accounts at scale after being promoted via paid social ads (Lakshmanan, 2023). Cloudflare later summarized the campaign’s cadence, noting the extension “was at one point being installed over 2,000 times per day,” and that installation unlocked backdoors and cookie theft aimed at corporate identities (Cloudflare, 2025). It is the same pattern in a different wrapper. The “AI” is the lure. The browser is the freight elevator.

What makes AI-branded packages so effective

Two things changed at once. First, developer demand for AI libraries exploded. Sonatype estimates Python package requests reached roughly 530 billion in 2024, up sharply year over year, with AI and cloud adoption as drivers (Sonatype, 2024). Second, the confusion space widened. A peer-reviewed USENIX Security paper finds “package confusion occurs beyond typo-squatting,” cataloging thirteen mechanisms—look-alike names, namespace tricks, metadata manipulation—that reliably mislead automated tooling and humans (Neupane et al., 2023). The academic language is careful, but the implication for small teams is loud. In the long tail, you are the quality control department.

There is also a new failure mode attached to AI itself. Preprints in 2025 documented “package hallucinations,” where large language models fabricate library names and developers then publish or install look-alikes, a dynamic some researchers call “slopsquatting” (Zhang et al., 2025). The machine invents a dependency. An attacker registers it. The cycle completes without a single spear-phish.

Fake APIs and the business of imitation

You do not need to publish code to sell a Trojan. You can stand up a convincing “AI API” with a pricing page and snippets that resemble a legitimate platform. The funnel works like this. A founder pastes in the quickstart. The SDK quietly requests access to local files for “caching” or “fine-tuning.” The wrapper calls out to an attacker-controlled endpoint. In parallel, phishing campaigns imitate the largest AI brands to harvest payment details and credentials. Barracuda documented “targeted emails impersonating OpenAI” asking recipients to “update payment information” and pointing at credential harvesting sites in late 2024 (Barracuda, 2024). These are not teenage pranks. They are revenue operations tuned to the tempo of small businesses.

When “AI agents” leak your private knowledge

The Trojan stack finishes the loop when you connect your tools. If a malicious SDK or convincing fake API makes it into your app, it is one hop away from your knowledge base. In August 2025, WIRED reported research disclosed at Black Hat showing how a single “poisoned” document could trigger ChatGPT Connectors to leak data from a linked Google Drive via an indirect prompt injection—no clicks required (Burgess, 2025). “There is nothing the user needs to do to be compromised,” one of the researchers said, describing a zero-interaction exfiltration chain that ended with developer API keys leaving the tenant through an embedded image request (Burgess, 2025). Microsoft’s security team now states plainly that “indirect prompt injection… is challenging to mitigate and could lead to various types of security impacts,” with data exfiltration one of the most “widely demonstrated” outcomes (MSRC, 2025). This is the part that keeps small operators awake. The stack is not just code. It is your inbox, your drive, your calendar, your CRM, and the AI agent you told to summarize all of it.

Why this hits startups and SMBs hardest

Speed compresses review. A solo founder does not have a security team or a procurement backlog. A ten-person studio running on contractors and cash flow cannot stage every integration across three environments. The Trojan stack knows this. It borrows the graphics of the tools you trust. It leans on your browser. It exploits the “quickstart” impulse in docs and the cultural comfort with copy-paste code. It thrives where leaders delegate dependency choices to AI pair-programmers and call it efficiency.

None of this requires a dramatic breach story. Most of it looks like routine development. One more pip install. One more extension to save time. One more “AI API” key generated for a feature test that never shipped. Weeks later you notice a drained ad account, a repo clone from an unexpected IP, a rash of secondary credential resets, or a Slack app you do not remember authorizing. The damage is downstream in accounting, growth, and morale. Not just in logs.

There is a line that runs across all of it. Attackers follow adoption. They copy the shape of whatever you are excited to plug in next and hide their business model where you told yourself you did not have time to look. That is the Trojan stack’s only hard rule. It does not need to outsmart you. It just needs to look like the thing you already wanted.

References

Barracuda Networks. (2024, October 31). Cybercriminals impersonate OpenAI in large-scale phishing campaign. Barracuda. https://blog.barracuda.com/2024/10/31/impersonate-openai-steal-data

ESET. (2024). ESET threat report H2 2023. https://web-assets.esetstatic.com/wls/en/papers/threat-reports/eset-threat-report-h22023.pdf

ESET. (2024, July 29). Beware of fake AI tools masking a very real malware threat. WeLiveSecurity. https://www.welivesecurity.com/en/cybersecurity/beware-fake-ai-tools-masking-very-real-malware-threat/

ESET Ireland. (2024, July 30). Beware of fake AI tools masking very real malware threats. ESET Ireland Blog. https://blog.eset.ie/2024/07/30/beware-of-fake-ai-tools-masking-very-real-malware-threats/

Fried, I. (2023, April 14). Thousands compromised in ChatGPT-themed scheme. Axios. https://www.axios.com/2023/04/14/chatgpt-scheme-ai-cybersecurity

Guardio Labs. (2023, March 9). "FakeGPT": New variant of fake ChatGPT Chrome extension stealing Facebook ad accounts. Guardio Labs. https://guard.io/labs/fakegpt-new-variant-of-fake-chatgpt-chrome-extension-stealing-facebook-ad-accounts-with

Kaspersky Global Research & Analysis Team. (2024, November 19). Kaspersky uncovers year-long PyPI supply chain attack using AI chatbot tools as lure [Press release]. Kaspersky. https://www.kaspersky.com/about/press-releases/kaspersky-uncovers-year-long-pypi-supply-chain-attack-using-ai-chatbot-tools-as-lure

Kaspersky. (2024, November 21). JarkaStealer in PyPI repository. Kaspersky Daily. https://www.kaspersky.com/blog/jarkastealer-in-pypi-packages/52640/

KnowBe4. (2024, November 7). Phishing campaign impersonates OpenAI to collect payment details. KnowBe4 Blog. https://blog.knowbe4.com/phishing-campaign-impersonates-openai

Lakshmanan, R. (2023, March 13). Fake ChatGPT Chrome extension hijacking Facebook accounts for malicious advertising. The Hacker News. https://thehackernews.com/2023/03/fake-chatgpt-chrome-extension-hijacking.html

Lakshmanan, R. (2025, June 4). Malicious PyPI, npm, and Ruby packages exposed in supply chain attacks. The Hacker News. https://thehackernews.com/2025/06/malicious-pypi-npm-and-ruby-packages.html